Certain Women has been my favorite movie of 2016. I have to write about it because I haven’t quite been able to figure out why it moved me so much.

We are in the Midwest, says the daring, drawn-out opening shot: the plains are wide, the skies gray, where the wind itself seems to come alive. A distant horn cuts through it all, and for about half a minute we are watching a freight train come into view and slide through the landscape, setting the tone and the rhythms, sounding the keynote to the aural landscape of what is to come. In Certain Women, so much tension surges from so little, with a pace so slow it aches. (It’s like the opposite of No Country for Old Men.)

Montana, specifically. Maile Meloy’s short stories, set there, in cities and distant hamlets, inspired the three-part screenplay: each grants us an oblique look into a woman’s life.

Laura (Laura Dern) is the lawyer of an obstinate client, who got into an accident at work and is now injured and unemployable. He wants to get back at his old boss, but having unwittingly agreed to an unsatisfying settlement, he has no case to make. He won’t hear it from her though. Only when another lawyer—a man—repeats what Laura has been saying for months does he resign. In a final, desperate effort, he takes a hostage. Laura gets sent in to negotiate. His scheme crumbles when he tries to escape but forgets to take his gun—out of exhaustion, perhaps, or out of sudden sympathy for Laura. The film leaves the question open/unanswered.

Gina (Michelle Williams) is married and the hard-working mother of an adolescent daughter. She and her husband—whom we first encounter the morning after he cheats on her with Laura—have decided to build a house out in the country. The neighbor Albert, a solitary man suffering from memory loss, would have just the right building materials for the house: some old sandstone from the settler days is lying around on his property. But with her husband being no great help, it takes all her willpower and charm to get Albert to part with his rocks. To cope, she goes on runs and smokes secretly in the forest.

Far out of town, an unnamed young woman (the brilliant Lily Gladstone) is living alone on a ranch and takes care of horses. During one of her roamings about town, she finds herself in a night class about school law for local teachers, taught by nomadic young lawyer Elizabeth (Kristen Stewart), who endures a four-hour commute in addition to a job back in her hometown in the morning in order to make ends meet. They talk, but only briefly, after the course in the local diner, before Elizabeth has to make her way home again across dark and icy highways. One day, the rancher decides to bring a horse.

The car moved fast in all that space, past the stumps of corn that blinked by in perfect rhythms. I hit the flat land again. It seemed I was part of some big purpose until the size of what was out there exhausted me. Eventually there were no states, there was only the sky that never got any closer and me moving through places I could not stay.

Throughout the movie runs a metaphorical subplot about the pioneers and colonizers who brutally, lawlessly cut through the lands of Indians—whose presence remains only as a spectacle, in the patterns on the rug in Gina’s tent, as a group dressed up and dancing before some bemused police officers and midday dwellers, later standing in line for a sandwich in full costume. Building your own house with stone from the land, braving the plains to make a living, tending to horses—these women are reclaiming what the Frontier has taken, they’re healing wounds and coping with it, but only in small ways, through things like taking pleasure in conversation, a cigarette, a sunset, even the possibility of love.

Big trucks were coming by bright and fast and disappearing into the flatness. The light at the edge of the sky was orange and thick with twilight. The gusts pulled at my clothes and I could see the men inside, their faces dark while they sat still and drove fast. They found work, driving to some place they didn’t know and then back toward the last thing they remembered being good.

The last thing we remembered being good, a sweet memory only recalled with stiff-jawed determination—that’s how it feels to watch the interminable present-tense lives of these people take shape. Kelly Reichhardt strips away the bullshit and steers clear of the dramatic turns and climaxes that the genre of the Western might have her led to indulge in, and what remains is barely thrilling, never quite reaching the level of plot or drama or narrative across its taut cuts, but simply what we know and love as life. At the same time, her straining aesthetic also asks us if we would recognize life if we ever came across it. These stories are repetition in a state of grace.

The quotes in italics are from Dylan Nice, Other Kinds, 2012.

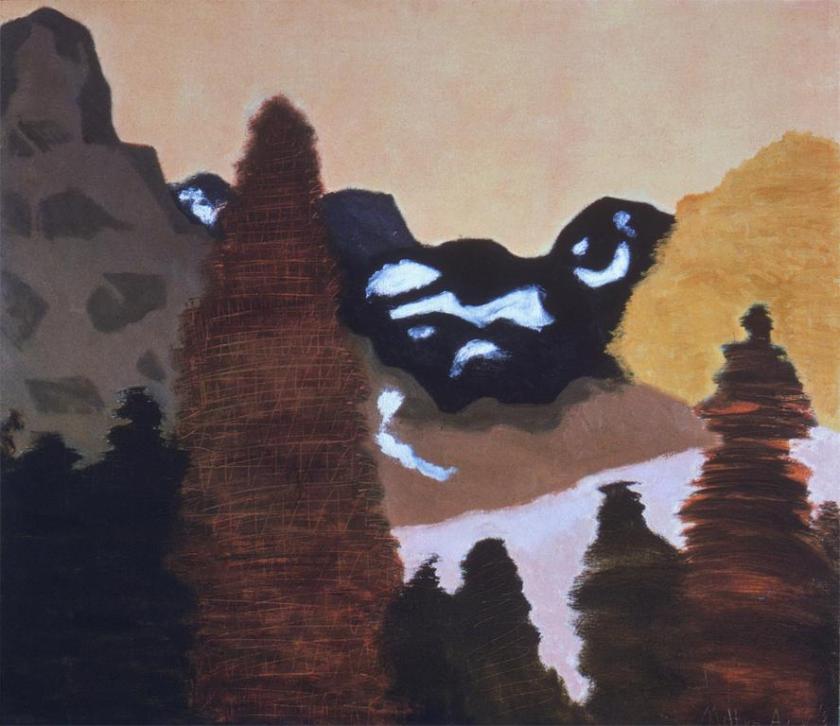

The artwork is from Alice Neel (what I’m imagining as the kind of portrait that Reichhardt would end up making if she were a painter) and Milton Avery (whose work inspired the movie’s color schemes).